10 Things "Car Guys" Teach Me About Leadership (Part 1)

I began this post a few days into the 2020 coronavirus shutdown. It was April, the time when hot rodders were supposed to be opening garage doors, fueling up, and burning rubber while looking for that next concourse, car show or drag race. To add horsepower to my anticipation, we had recently moved to Pennsylvania, a state with one of the best car cultures in the country. PA has Hershey, Carlisle, The Pittsburgh Vintage Grand Prix. I was looking forward to participating.

Then came COVID 19, the viral stop sign.

What Ralph Nader, the Prius, and the State of California could not do, Coronavirus did. It put the brakes on most automotive activity. Events canceled. Car shows postponed. Perennial favorites like the Hot Rod Power Tour disappeared from the calendar. COVID was one long red light on the hot rod highway. Sure, I could build a virtual car collection, but that was nowhere near as fun as driving my ‘36 Chevy.

So there I was in the early days of COVID, hunkered down in my home office, when my automotive daydreams collided with my day-to-day leadership responsibilities. As I pondered my predicament, I realized there are many leadership lessons to draw from the world of hot rodding. The car culture is so much more than “fast and loud.” It is expertise and engineering, innovation and collaboration, artistry and action, teamwork and tools. The more I mused, the more I concluded: The world of automotive performance is leadership on four wheels. Car guys (and gals) have a lot to teach me about leadership. Here are 10 lessons they are teaching me.

1. Hire the best.

Turn on MotorTrend. You will discover the best hire the best. Chip Foose worked with “The A Team” for years. Dave Kindig has “the best mechanics, technicians, and fabricators in the business.” At Classic Car Studios, Noah Alexander has a “team of visionaries and master craftsmen,” and Justin Nichols proves that a small town shop can deliver big time rides — but only with exceptional help.

The same is true in leadership.

I get to serve as the president of a college. It is a huge honor and massive responsibility; however, my effectiveness hinges to a very large degree on the team with whom I work. Our team is good and that is a good thing. The better they are, the better we are. But what does it means to be “the best”? Here’s what I look for:

Character and competence — Asaph puts Israel’s history to music in Psalm 78. It is a tune every leader should hum, especially Psalm 78:65-72. The psalmist points to King David, highlighting three essential facets of his leadership: calling (which I address below), character, and competence. The psalm ends with these words: “And David shepherded them with integrity of heart; with skillful hands he led them” (Psalm 78:72 NIV). It is not enough to have the heart of integrity (as important as it is), the leader must also have “skillful hands,” i.e. the ability to do the job well. Leaders who hire for one, hoping to get the other or train for the other, are making a mistake.

Proactivity and patience — I want leaders who come to me with ideas. If I have to be the smartest person at the table, we are in trouble. I tell our team, “If you are around this table, I am expecting you to speak up, bring ideas, and where necessary, challenge the ideas and solutions on the table.” Leadership is about going from “here to there.” What got us here won’t get us there. The best leaders are constant thinkers, tinkerers, and learners. They scan the the horizon for new ideas. At the same time, they have the wisdom and patience necessary to avoid flooding the system with a constant flow of new ideas and initiatives. They are patient. They give ideas — and people — a chance.

Task and relationship — Leaders must be able to give time to both the task and the people whose time on task helps us move forward. The best have left a track record of progress and pouring into the people who make the progress possible. These leaders are collaborators, able and desirous of working with others. They embrace problems. But they attack the problem, not people. They fix problems, not blame. The best leaders are highly attuned to doing two things well: getting the job done and caring for people.

Potential and performance — When I spot (or someone else does) a “rising star,” I want to know how this person with all this potential has performed. Jesus said, “If you are faithful in little things, you will be faithful in large ones” (Luke 19:19 NLT). Some prospective leaders are just neon lights, their brilliant personality masking a lack of initiative, stick-to-itiveness, or willingness to do the hard work of “figuring it out.” When I asked one prospective hire how he would handle the difference in scale from the church he was serving to ours (which was considerably larger), he didn’t tell me what he would do, he told me what he had done. Like David of old, he said, “I can’t tell you what I will do, but I can tell you what I did when I faced the bear and the lion” (read 1 Samuel 17:33-37). He got the job — and performed with God-honoring excellence).

Calling and responsibility — I’ve been a church planter. Shannan and I moved our family a thousand miles to start a church in a different state. We lived on $900 a month. I’m not alone. I have a friend who planted with one or two month’s salary and then was expected to make it. (He did!) We did this because that was the vocation God had for us. We embraced it gladly. In our case, there were financial increases over the years, but there came a time when our growing family necessitated a raise. I remember having a conversation with our church leadership, “Guys, it’s time!” I said. “I can no longer carry on at this rate. I need an increase.” Paul said, “I will gladly spend myself and all I have for you,” (2 Corinthians 12:15). He was called and it is what called people do. And Paul said, “the laborer is worthy of his hire” (1 Timothy 5:18). There is a tension there. “The best” live in that tension, gladly pouring out themselves because they are called, and recognizing the call need not always be at a substandard salary.

2. Master your craft.

Metal fabricators are an essential subset of the hot rod community. Ian Roussel is a metal-working genius. Ian and his tribe of alloy artists remind me no one turns out great work simply by turning on a welder whether that be Stick, Mig, or Tig! You have to master the craft and that takes time.

Photo credit: https://www.noticiasdatvbrasileira.com.br

Leaders invest the time to master their craft.

When I was in the final stages of my interview process for Lancaster Bible College|Capital Seminary & Graduate School, an outside consultant (Jay Desko) spoke this truth into my life: “You don’t know the academic model. You’re going to have to grow in this area.” He was spot on! This has been my biggest challenge in my presidential role.

So how does one “master” his/her craft? I am learning that it is a combination of both attitude and action. Here are three essentials:

Humility (Proverbs 18:12): Do I set aside my ego and ask for help? When was the last time I said to a peer, “Can you help me get better in this area?” I have noticed that “the best” admire the work of others and easily move from teacher to student. I have to ask myself, “Am I teachable?” “Am I coachable?” “Am I willing to to put myself in the place of a learner when I think I am the one who should be giving the lecture?”

Curiosity: Those who master their craft are incessant learners and tinkerers. We live in a day of blogs and books and videos and conferences and workshops. There is no excuse for not getting better. What is the burning question I have about the area I want to improve? If I don’t have questions I’m asking or resources from which I am gleaning, I’m not really serious about mastering my craft.

Tenacity (Proverbs 14:23): Getting better takes hard work. When was the last time “improving” cost me sleep or that coveted commodity we call “time off”? Do I know my growth area? Do I have a developmental plan for improvement? Have I identified a mentor or coach to help me improve? Don Meredith, former quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys and then Monday Night Football commentator loved this proverb: “If ifs and buts were candy and nuts, we’d all have a Merry Christmas.” What is my self-development plan for my growth area?

What is your next step to master your craft?

3. “Figure it out!”

I enjoy watching car shows, particularly of the “fixer up” variety. The best of the best are totally unafraid of encountering a problem to which they don’t know the answer — and letting you know they don’t know the answer. The reason is that they operate with the hot rod maxim, “figure it out!” Hot rodding is an endless trek into the unknown. Nothing is easy. Most things take much more time than we imagine. The one bolt you need to finish the job is going to be where you can’t reach it and when you finally do it is rusted solid or will require the dexterity of an Olympic gymnast to put a wrench on it.

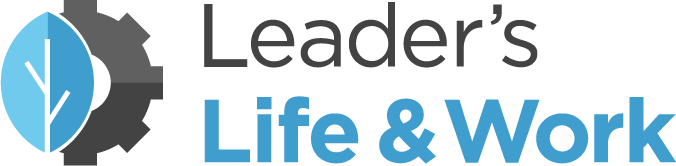

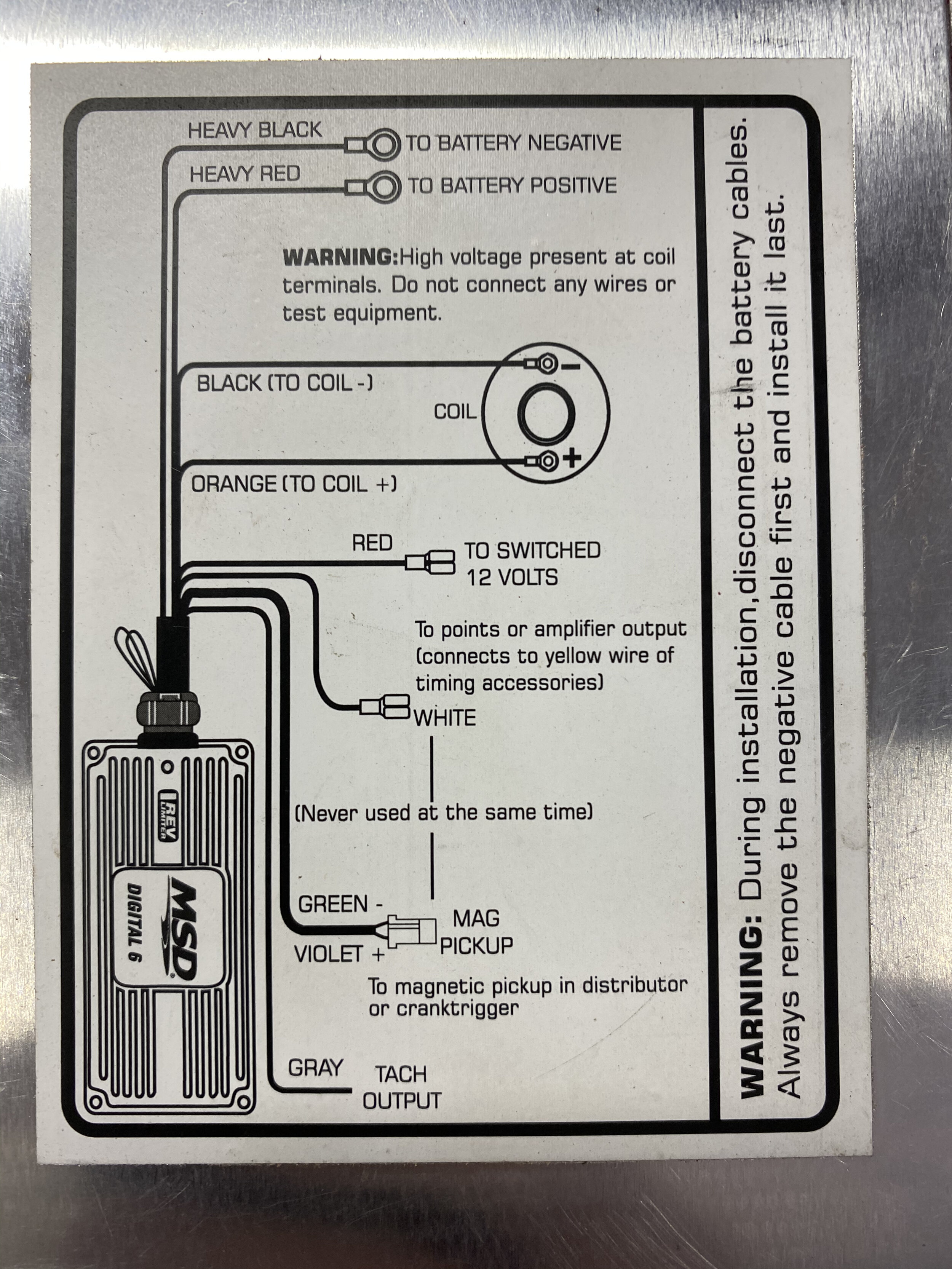

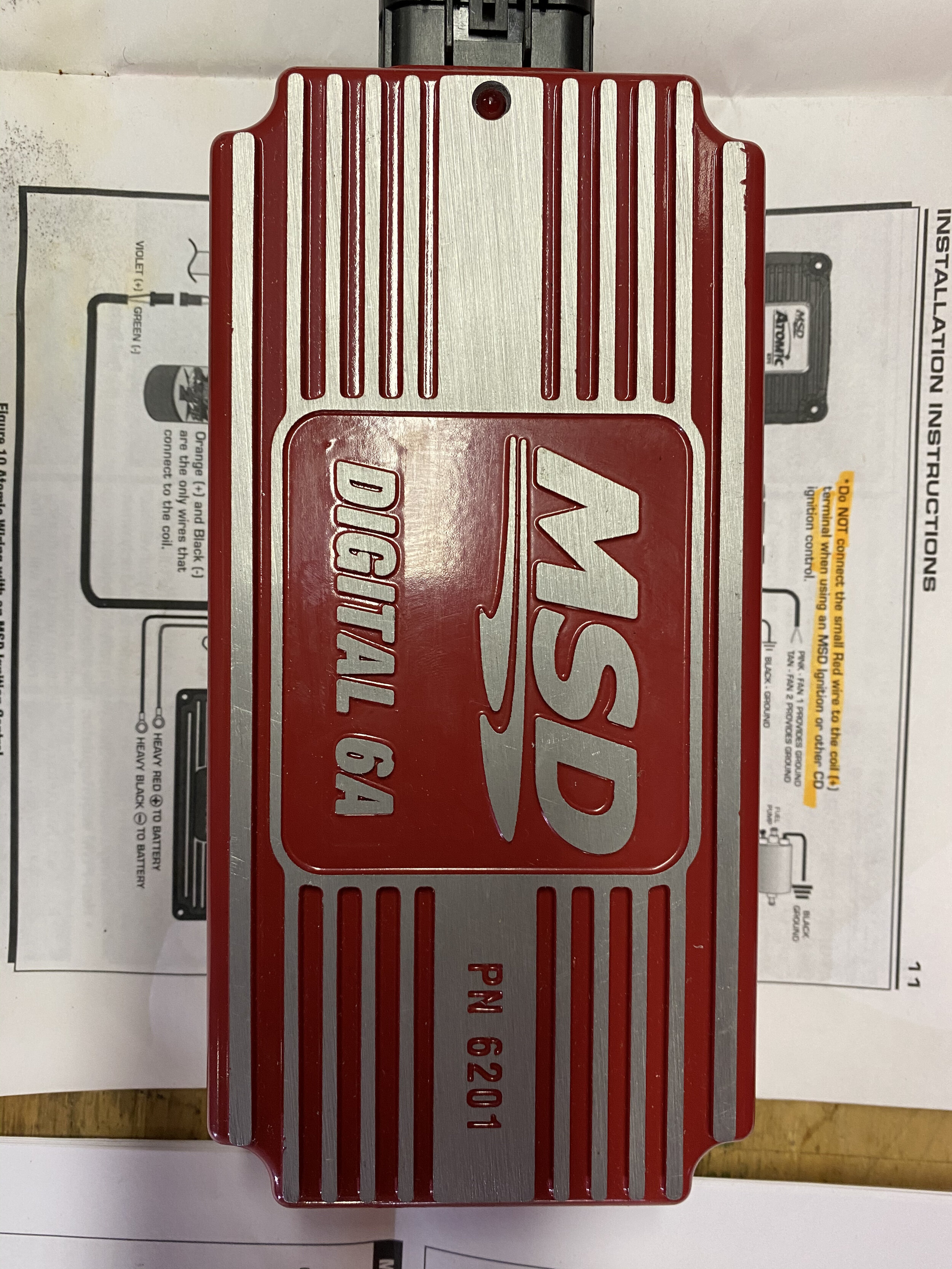

One of my many “figure it out” moments came when I had to install the MSD component you see below. I wanted it hidden but accessible. That meant fabricating a mounting bracket, which meant creating a pattern, sourcing metal, bending, cutting, welding, painting, test-fitting, and finally installing the component; all for a very important and hidden aspect of my build, a vital part no one sees.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. is recognized for saying:

“I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.”

Life is complex. Leadership is complex. There are few nice and tidy days. Problems are going to come. Problems missional, systemic, financial, cultural, relational, and strategic. Leaders rely on God, seek the help of colleagues, and do the best they can to “figure it out.”

Figuring it out is part of the quiet work of leadership. It means I will have to pull out of the fast lane and devote time to doing what I often feel I don’t have time to do: pray, think, and consider options.

4. Work with a “priority list.”

I like to look at hot rod build sheets. The best projects follow a plan! Whether it is drawn up on a piece of cardboard or a detailed spreadsheet, a “first law” of hot rod builds is work from a plan (and a budget). Kyle Smith, who writes for Hagerty, says: “If there is one key to staying sane—and keeping to any type of budget—while tackling car and motorcycle projects, it is an iron-fisted grasp on what has been done and what needs to be done. The easiest way to do that is with a simple, hand-written to-do list.”

Leaders are masters of prioritization and communication. In The Four Disciplines of Execution: Achieving Your Wildly Important Goals, authors Chris McChesney, Sean Covey, “The first thing I want to know when I am talking to a leader is, where has that leader chooses to spend disproportionate energy?” Tim Tassopoulos p. 117and Jim Huling have much to say about the necessity of prioritization. Here are three admonitions that continue to resonate with me:

““Attempting to spread limited capacity across multiple goals is the most common cause for failure in execution.” p. 19.

“The first thing I want to know when I am talking to a leader is, where has that leader chooses to spend disproportionate energy?” Tim Tassopoulos p. 117

“Clear measurable targets are the language of execution . . . concepts stir the imagination, but targets drive performance.” P. 129

Do I have an “iron-fisted grasp” on what has been done, what needs to be done, and how we will spend our limited capacity to get it done?

5. Know when to “Farm it out.”

While there are some hot rod shops that “do it all” (build, fabricate, wrench, paint, sell), most recognize their specialty and lean on others where they are deficient. A great designer might use a shop that specializes in building engines; a painter might lean on a builder, and a builder might rely on an outside paint shop to give his ride the exceptional finished look.

Everyone needs someone to help them be at their best.

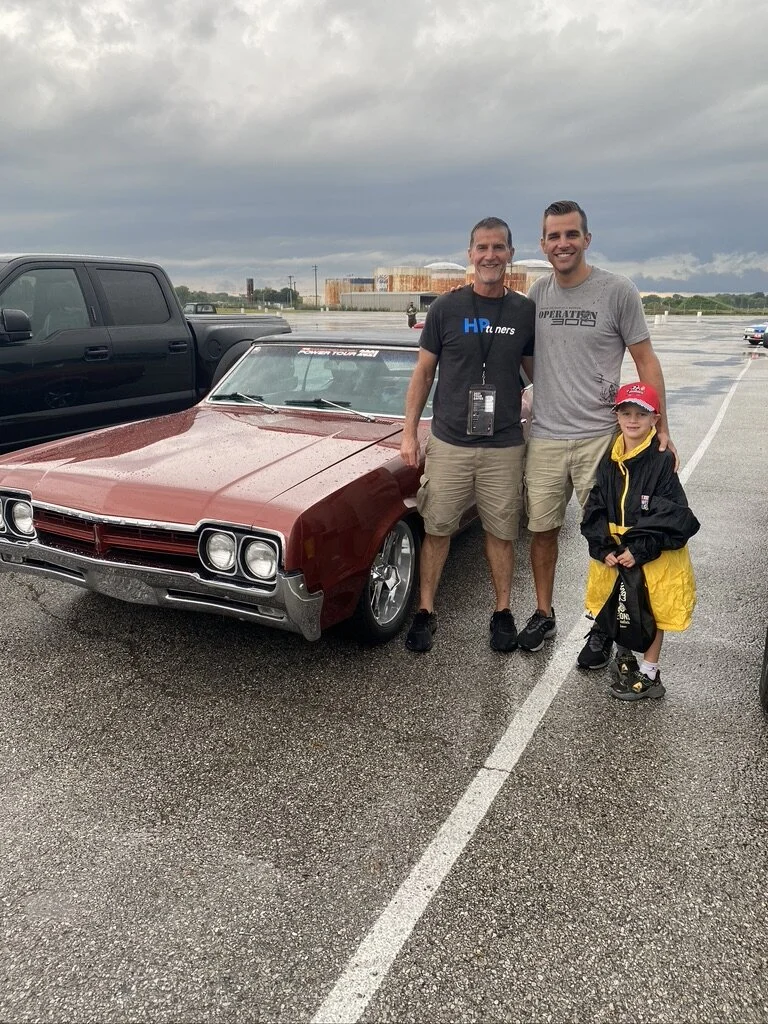

Earlier this summer, I set my sights on “finishing” my 1966 Oldsmobile Cutlass. I had a Wildly Important Goal: To see the car move under its own power in time for the Hot Rod Power Tour. I was making stellar progress, but despite my intense focus, I simply ran out of time. I had to decide if I was willing to “farm it out” to a local hot rod shop to finish some aspects I could not address. I sent the Cutlass “to the farm” (Louie’s Hot Rod Garage).

Louis and his team finished what I could not. I got the car back in time. Made some last minute adjustments, and we were “on the road.” It is a road we would not have traveled, good times we would have missed, and memories that would not be ours to share — IF — we were unwilling to “farm it out.” Farming out was costly and it helped me achieve my goal and enjoy great time with Shannan and with our son and grandson who were able to join us for a few legs of our trip.

There is a pay-off to farming it out!

No one does it all. Assessing and acknowledging one’s leadership deficiencies and limitations is an essential leadership function. Who do you need around you to round out your leadership? What do you need to “farm out” for you and your organization to be at its best?

What’s your next step?

I remember watching one hot rod program when the builder wrapped up his show by saying, “Get out there and build something!” That’s what leader’s do. They build. They advance. They take calculated risks. They help organizations go form “here to there.” And the world of automotive performance provides some insights on how we can all do it better.

What is your key leadership takeaway from the world of hot rodding? What is your next step in building your leadership?

Notes:

“If there is one key to staying sane . . .” from “5 to-do list tips to keep your projects on track” by Kyle Smith. https://www.hagerty.com. Accessed November 3, 2021.